The Body in Pieces: Mangled Language

It could just as well be a dead donkey, for example…Things have broken free from their names. They are there, grotesque, stubborn, gigantic, and it seem ridiculous to call them seats or say anything at all about them: I am in the midst of Things, which cannot be given names.[i]

From the bimbo, to the vampy femme fatale; from bitch and ballbreaker, to spinster and hag – the stereotypes foisted onto women support the claim that gender informs a system of social expectations, yet suggest that it is often played out at the level of representation of sexual difference.

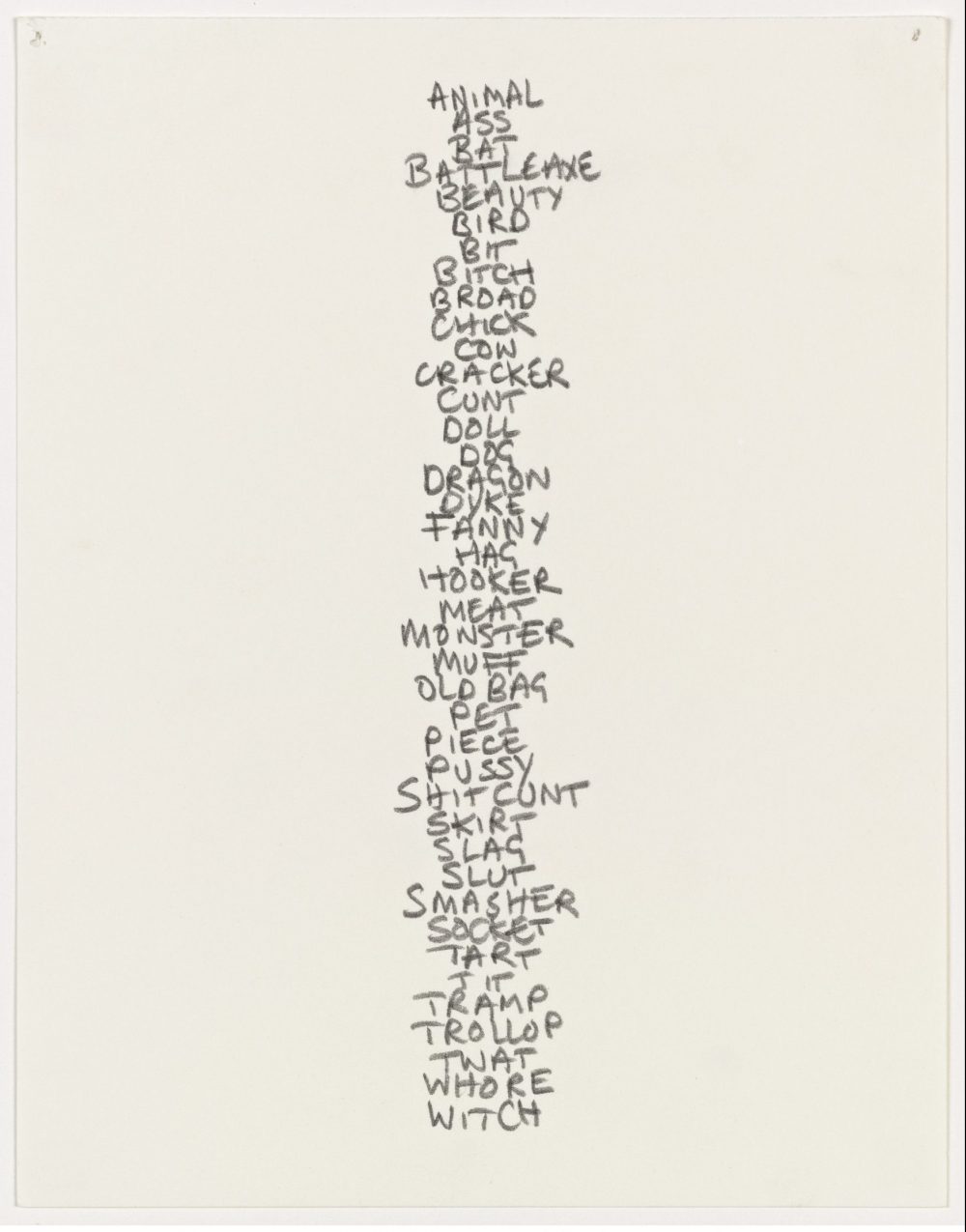

Sarah Lucas, Five Lists 1991

A series depicting slang words about women, genitalia, bodily excretions and sexuality, Lucas’ lists are not exhaustive compilations of associated ideas, and are far from subtle – they monumentalise a certain crudeness of popular culture. These bald pronouncements may offend, or tickle, certain sensibilities, such is the power of words. Thus Five Lists compels me to address the issues raised by this compendium of puerility, before moving on to Lucas’ worldview, which presents us with a different way of conceptualising sexual difference.

Kristeva (1982), in respect of abjection towards the sign of sexual difference, argues the social processes, sorts and demarcates bodies to render them proper, conforming to, but not exceeding cultural expectations. The excessiveness of things pushes the limit set for the organisation of the body and its processes: bodies become de trop, ‘superfluous, that is to say amorphous and vague, sad.’[ii]

Ranging from the base and the animal to the supernatural, this alphabetised list is not only a colourful compendium of the names of body parts: it also refers to the woman to whom such parts belong. Far from subtle, these slurs monumentalise a certain crudeness of culture, the mangled language that informs sexism. As their centralised, columnar arrangement on the page suggests, the words are central to the way in which women are often spoken about in colloquial speech.

It is a representation of desire, and not an impetus for it. It is a work of classic pervery;[iii] one that moves beyond its own explicitness, wresting the body back from rationalism, and allowing it to wallow in its own immanence. Five Lists reminds us that for an artwork to possess aesthetic value, and to be engaging, does not imply eschewing insalubriousness. If it offends or shocks in a visceral way, this nausea is what prompts us back into the body.

Sexual difference is really a fundamental difference, as any ascribed to material entities. One can identify with being female or male, as one can with religious views, or what race or ethnic group one belongs to. To a certain degree, these can vary, presenting their own difficulties or set of challenges: I may identify as a woman; I may take up a nationality that is different to the one I was born into; I may convert to a different religion; I can obscure my ethnicity, speak a different language and erase linguistic accents and quirks; I can change my identity as easily as I may change my name. But why is it that I cannot escape the elements that come to signify my sex? Five Lists, clearly a work that addresses embodied looking, raises questions about the experience of the lived body.

The Absurd

‘To understand is to experience the harmony between what we aim at and what is given, between the intention and the performance – and our body is our anchorage in a world.’[iv]

The objective material body is intentional. That is, at the level of consciousness, it apprehends things. Human embodiment also implies an incarnated mind.[v] The mind (life, soul) is bound to our corporeality, with physiology and materiality framing the set of possibilities that present themselves to us. But as humans are also psychological and cultural beings, the body does not entirely bind existence. Mental and physical processes – mind and body – intertwine or overlap. The body is not an inert mass to be orchestrated and prodded into action, but the ‘living envelope’ of our intentionality as the incarnated subject.[vi] I will examine the nature of this dialogue through the absurd.

‘From the moment absurdity is recognized, it becomes a passion, the most harrowing of all.’[vii] Here, Camus refers to Sartre’s Nausea: ‘This discomfort in the face of man’s own inhumanity, this incalculable tumble before the image of what we are, this “nausea,” as a writer of today calls it, is also the absurd.’[viii]

Nausea and the absurd both derive from a mounting feeling of anguish at the discovery that the structures and frameworks of our existence are fragile, and subject to collapse. It is Camus’s claim that an appeal to transcendence is a ‘betrayal’ of the human condition, a condition in which Lucas’ project is entirely situated. Camus, like Sartre, makes the case that despite our awareness of the absurdity of life, the meaninglessness of it is offset by the voluptuous vitality of the physical world and the objects that surround us.

For Sartre, awareness of absurdity is an understanding of a lived relationship to the world and of the ambiguous unity represented by subject/object and mind/body existing across planes of signification rather than mutually-exclusive categories of being.[ix] A collapse of these planes, or a re-direction through a different signification of the thing that is known, is channelled through the absurd, triggered by the experience of nausea, best illustrated by Roquentin’s attempts to identify with objects and glean meaning from them. Nothing has intrinsically been disordered, outwardly all remains the same, yet he is assailed by a mood.

Lucas’ works do something similar. For the reader of Five Lists, nothing has changed, yet they may not be able to see themselves in her words and be either nonplussed, or profoundly troubled by this eye-opening disclosure. Unlike Roquentin, floored by the arbitrary nature of world, Lucas has taken charge, pointed ‘a finger to what is there,’ celebrating the restless sensationalism of the everyday. In this endeavour, Lucas – unlike Descartes who only let back in the world those things which could be proven; unlike a Lacanian philosophy of lack – explores being, not from the start or the end of situations, but as entirely present in the contemporary experience: the ‘ongoing banter. It can trigger something that can be handily applied later on.’[x]

‘all roads are blocked to a philosophy which reduces everything to the word “no”. To “no” there is only one answer and that is “yes.” Nihilism has no substance. There is no such thing as nothingness, and zero does not exist. Everything is something. Nothing is nothing. Man lives more by affirmation than by bread.’ ( Hugo, 1862)[xi]

The possibilities resulting from nihilism create a chasm, a gap – a nothingness according to Heidegger – a meaninglessness according to Camus. This is the absurd, or that with which one has difficulty coming to terms. Grosz, referencing Kristeva, calls this the abject: the ‘what of the body falls away from it while remaining irreducible to the subject/object and inside/outside oppositions,’ being both but resisting identification with either.[xii] Merleau-Ponty asserts sexuality is not a phenomenon to be subsumed into existence,[xiii] in the same way the body cannot be nothing. The body, a model for understanding corporeality,[xiv] is not incontestable, and expresses modalities of being that cannot be qualified ‘in the same manner as the stripes signify an officer’s rank or as a number designates a house. The sign here does not only indicate its signification, but is also inhabited by it; there the sign is what is signifies.’[xv] The words of Five Lists are not meaningless, nor nothing: they are the sign that designates sexual life within a particular ‘current’ of existence that is bounded by the ‘sexual organ.’

References and Additional Reading

[i] Jean-Paul Sartre, Nausea 1938:180

Jean-Paul Sartre (1938) Nausea (London: Penguin Books, 2000)

[ii] Sartre, 1938, p. 188. De trop is a Sartrean term.

[iii] The lists are not pornographic or gratuitous – conditions Lucas defines as ‘Ordinary Pervery.’ Ordinary Pervery is not Classic Pervery, which is a ‘rare’ condition that the individual must conceal until coming of age. Who are ordinary ‘pervs’? According to Lucas, most people. Classic pervs take pleasure in the undesirably unusual (Lucas, I Scream Daddio, 2015, pp. 132-133).

[iv] Merleau-Ponty, (1945: 144). Being, in Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, refers to the lived experience of the body through the senses.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1945), Phenomenology of Perception (Routledge: London and New York, 2012)

[v] From the Latin incarnare, made flesh. The flesh made manifest.

[vi] Merleau-Ponty, 1945: 145

[vii] Camus 1942:20

Albert Camus (1942), ‘Absurd in The Myth of Sisyphus,’ in God, ed. T.A. Robinson (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 2002), pp. 317-327. A non-fiction essay on the ethics of suicide – here the absurd is the expression of a fundamental disharmony in our existence.

[viii] Camus (1942)

[ix] Sartre, (1943:97-119) implies that the gap between a being/person (for-itself) and the world and its objects (in-itself) is another way of experiencing the absurd. The for-itself lacks the ability to come to terms with its own existential ‘nothingness,’ which is why it seeks an affinity with objects: or rather it has the potential for nihilism, or for ‘othering’ the in-itself, and this implies possibility to the facticity of the in-itself. This affinity signals an emotional apprehension of things which Sartre describes as overflowing with a knowledge of the world the for-itself does not possess, for being just ‘is.’

Jean Paul Sartre (1943) Being and Nothingness: A Phenomenological Ontology, trans. Hazel Barnes (New York: Philosophical Library, 1956)

[x] Lucas (2011) speaking to Pauline Daly on how she names her characters – from phrases ‘Out of my past. Overheard in the present.’ (After 2005 Before 2012, p. 50)

[xi] Victor Hugo (1862) Les Misérables (London: Penguin Classics, 1982), p. 1210

[xii] Grosz,( 1994, p. 192). moves away from the sphere of subjective representation, to insist, much like Young (1990), on the female experience of the lived body.

Elizabeth Grosz Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism (London: Routledge, 1994)

[xiii] Merleau-Ponty, 1945: 161-164

[xiv] Corporeality as defined in Grosz, 1994.

[xv] Merleau-Ponty, 1945: 161-164

[xvi] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press,1982)

Lucas, Sarah Five Lists (1991)

Image courtesy of Museum of Modern Art , New York (MoMA), licensed through Scala Archives