The Phenomenology of the Breasted Self

In Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, the chest is the centre of our being-in-the-world.[i] The philosopher Iris Marion Young agrees: ‘the chest is importantly the center of a person’s being,’ albeit with a sensibility particular to the nature of breasts atop these chests.[ii]Women’s chests have breasts: ‘the primary things…this reification of breasts is at the heart of the reification of women.’[iii] Without conscious effort, when one wants to indicate to others who one is, one generally points to oneself at the level of the chest to signify I, not to the head or brain, the ‘seat of consciousness, identity.’[iv] For women, this simple identifying movement is laden with signification.[v]

Breasts, a primary signifier of female bodies, are everywhere. These lumps of variable, vulnerable, multi-functional tissue affect physical movement and subjective and psychic identity. They form the landscape of the everyday, as objects of fascination, desire and even disgust. And yet women’s own accounts of breasts, or the lived experienced of having breasts, as opposed to being a breasted entity generally, do not extend beyond the discourses of medicine and pathology.[vi]

The ‘slit aesthetic’ is a term used by Young (1990) to refer to clothing that is cut and arranged to reveal the erogenous zones of the female body. The slit aesthetic is a sublimated attempt at titillation, a contrast to sexualised images of the female breast that assault the eyes in places where one would not necessarily expect to see them, such as on public transport, offering little in our understanding of what it means to exist within the public body as a breasted individual. The acceptability (in Western countries) of showing cleavage, but never the nipple (considered obscene and classed as a misdemeanour in some countries), indicates the breast to be an active, independent zone of ‘sensitivity and eroticism,’ mediated by ‘patriarchal taboos,’[vii] or instances when the fetishism that permeates the breast ebbs, making it just another signifier of feminine functions, such as breastfeeding.

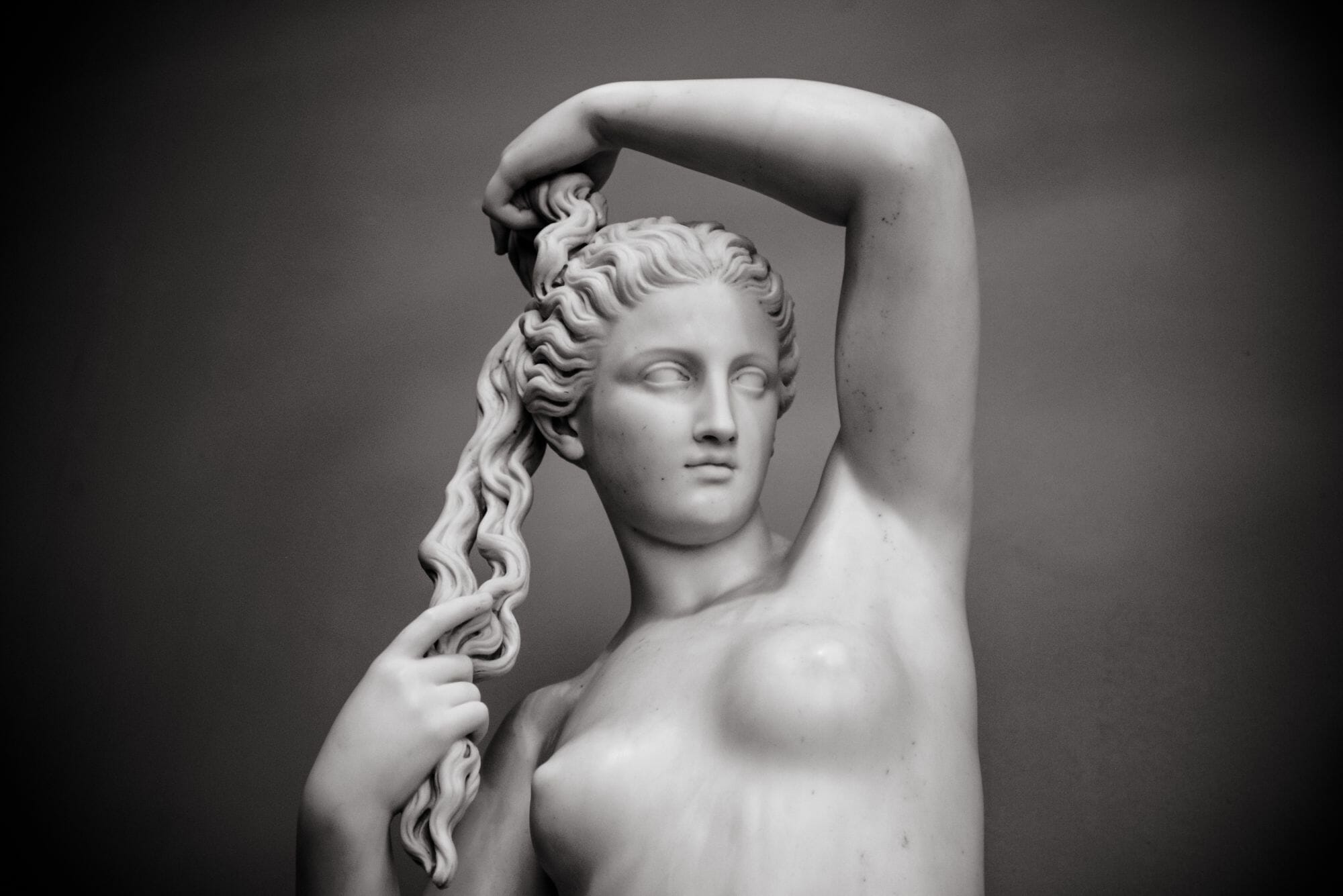

The ideal breast shape –coaxed by restrictive garments or surgery – is round, full and perky. Aged or lactating breasts hold no interest in Western visual culture, which has laid a claim on the female form by suggesting – from the sculptures of classical antiquity, after the fourth century BCE to the tabloid breasted body – that a woman’s body is an ideal of beauty.[viii] Mary Beard argues that the preponderance of breasts in visual culture is not incidental. Yalom adds that the breast’s evolution into a symbol of excess and lechery in society has to do with politics and economics, noting that in Asian and South Pacific cultures where the breast has not been sexualised, the bared breast is viewed indifferently.[ix]

Sarah Lucas, Mumum (2012)

Popular expressions that are used to refer to women, such as bitch or ‘tits and ass,’[x] become, involuntarily, central to a sense of self in many capacities: through anxiety, mortification, and in some cases, pride. Breasts are fluid matter: ‘in movement they sway, jiggle, bounce, ripple …’[xi] They are like ectoplasms. Without a supporting garment they would shift and shape in tandem with the body’s movements. In this sense they are not inert matter, and in the social and cultural sense they take up a persona that defies the Cartesian worldview,[xii] a persona characterised by Young as ‘breasted individuals.’[xiii] Breasted is a term usually reserved for describing a jacket, or for identifying birds. Unlike that other sexual marker, the vagina, breasts are easily co-opted and appropriated. Menstruation is a deeply personal and hidden aspect of the feminine lived body,[xiv] so breasts are truly the only visible sign of a girl’s trajectory into womanhood: they are objects of shame, inquiry, exploration and exploitation.[xv] British artist Sarah Lucas’ notion of ‘perviness’, however, celebrates, albeit awkwardly and impishly, the pleasure of the breast through visual and tactile examination in ways that offset the indignity of being qualified as a walking pair of breasts.

Breasts are ‘de trop’ (Sartre’s term),[xvi] the ‘contingency of presence,’ hidden behind clothes and artifices, but never disguised. When these are thrown off, what remains is the ‘pure intuition’ of flesh, what Sartre defines as ‘not only knowledge,’ but the ‘affective apprehension of an absolute contingency[xvii] The ontological contingency of being-in-the-world is reflected in the gap between oneself (or what one thinks one knows) and objects (more a reflection of reality than one is willing to concede). Subjective embodiment is the way humans make sense of the world – it is the channel through which people ‘make space, the object or the instrument exist for us and through which we take them up, as well as to describe the body as the place of this appropriation.’[xviii] However, as Young argues and Lucas demonstrates, when the focus is on the perceived thing (the breast, for instance) and not the relation between the embodied subject and the world, it is easy to miss how this correlation becomes an exchange between, and, for the epistemological subject and the object. Therefore, in phenomenology, ‘bodily organisation’ is governed by affective states, affected, in turn, by the objective world.[xix]

References and Additional Reading

[i] Merleau-Ponty could be described as a philosopher of the body. Whereas Husserl had already addressed embodiment as Leib (intentional living aspects as opposed to the body’s thing-like aspects, or körper), Merleau-Ponty, by drawing out ‘the un-thought thought’ of Husserl’s work (The Body and the World, p. 27) declared the body as the site of the material and of consciousness. It is the subjective, lived body that is in constant dialogue with the world. Merleau-Ponty calls the lived unity of the mind–body-world system ‘the lived body.’

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1945), Phenomenology of Perception (Routledge: London and New York, 2012)

[ii] Young, 1980, 1990. Young uses de Beauvoir’s theory of constraint and Merleau-Ponty’s thoughts on perception to consider the ways in which women are unable to occupy the spaces they inhabit: they see themselves as objects, not subjects. Young notes that a body’s relationship to space and to objects, according to social and cultural norms, dictates the modalities of movement and of being.

Iris Marion Young develops Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology to focus on embodying and occupying gendered spaces, in ‘Throwing like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility and Spatiality,’ Human Studies 3:2 (1980), pp. 137-156.

Simone de Beauvoir (1949) The Second Sex (London: Jonathan Cape, 2009),

[iii] Young 1990: 195

Iris Marion Young On Female Body Experience: ‘Throwing Like a Girl’ and Other Essays (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005)

[iv] Young 1990: 189

[v] Prior to Young’s challenge of the phenomenological body – male by default – de Beauvoir (1949) had posed a challenge of her own, conceptualising the embodied subject through the erotic and how the erotic perceiving body is situated in the world.

[vi] There is a dearth of literature on women’s experience with breasts, Young being one exception. On the other hand, there is a lot of material on vaginas. See Emma L. E. Rees, The Vagina: A Literary and Cultural History (London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

[vii] Young, 1990:196

[viii] Mary Beard reflects on the reason for the sudden appearance of female statues after this date, with the Venus Pudica thought to be an early example. The Greek statue of the Aphrodite of Knidos, popularly known as Venus Pudica, is thought to be the earliest, and is typical in its attempt to conceal the genitalia with the artful placing of the model’s hand.

Mary Beard, Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures and Innovations New York and London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2013)

The ancient Greek figure of the single-breasted warrior Amazon (from the Greek a (without) mazos (breast)) was, in contrast, deliberately contrived to be threatening. The Amazons were women ‘who had cut off one breast so they could draw a bow. The remaining breast nursed only female children: male infants were discarded.’

Adrienne Mayor, The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014)

[ix] Marilyn Yalom, A History of the Breast (New York: Ballantine Books,1998), p. 49

[x] American slang for ‘tits and bums,’ itself British slang for woman. Oxford Dictionaries Online.

<https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/tits_and_ass> [ 20 November 2015]

[xi] Young 1990: 195

[xii] See Susan Bordo (1989) quoted in Young (1990) who argues ‘that 20th century advanced capitalist consumer culture has gone beyond the Cartesian mechanical understanding of the body, to a view of the body as plastic, moldable, completely transformable and controllable according to a variety of possibilities.’ (p.91)

Susan Bordo, Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993)

[xiii] Young 1990

[xiv] See Iris Marion Young, ‘Menstrual Meditations,’ in On Female Body Experience, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 97-122. Young discusses how female bodies move as a result of the parameters enforced by having breasts.

Young is credited with transforming our understanding of lived phenomenological experiences by grounding this discourse on events and situations specific to female bodies: breasts; pregnancy; menstruation; body positionality and space.

[xv] Young (1990) commented on the absence of women writing about their experiences with breasts (not just the body in general). Writing about breasts tends to focus on medical, health or aesthetic concerns and breasts are a recurring site for exploring issues around gender, subjectivity, desire and power. But writing about feelings or ideas related to this changing part of the body – on both the physical changes and the function and meaning of breasts – is scarce. One notable exception is a 1979 collection of essays on the body experience of having breasts called Breasts: Women Speak About Their Breasts and Their Lives, edited by Daphna Ayalah and Isaac J. Weinstock (New York: Summit Books).

[xvi] Sartre in Being and Nothingness.

[xvii] Sartre, 1943: 367

[xviii] Merleau-Ponty 1945: 156

[xix] Ibid

Sarah Lucas, Mumum, 2012

not signed or dated

tights, kapok, chair frame

145 x 110 x 90 cm

© Sarah Lucas, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London